During Sunday dinner, my six-year-old daughter, Lily, asked, “Mommy, can I have some of grandma’s special candy?”

I raised an eyebrow. “What candy, Linda?”

My husband chuckled. “Spoiling her again, Mom. It’s the candy from the special hiding spot.”

Lily bounced in her chair. Before anyone could stop her, she jumped up and ran to the kitchen. We heard cabinets opening. “Found them!” she emerged, clutching a bag of peanuts. “These? Grandma’s special candy.”

My heart stopped. “You’re… you’re allergic. Has grandma been giving you these?”

She nodded enthusiastically. “Every time. She says I’m brave.”

Mike stood up so fast his chair fell backward. “What the hell?”

“Small amounts build immunity,” Linda said calmly.

The room tilted. Those stomach bugs. Every Sunday night for two years, Lily crying about her tummy. The Monday morning fevers, the random hives we couldn’t explain. “You’ve been feeding her peanuts,” the words came out like venom.

Linda stood up. “You’re being dramatic.”

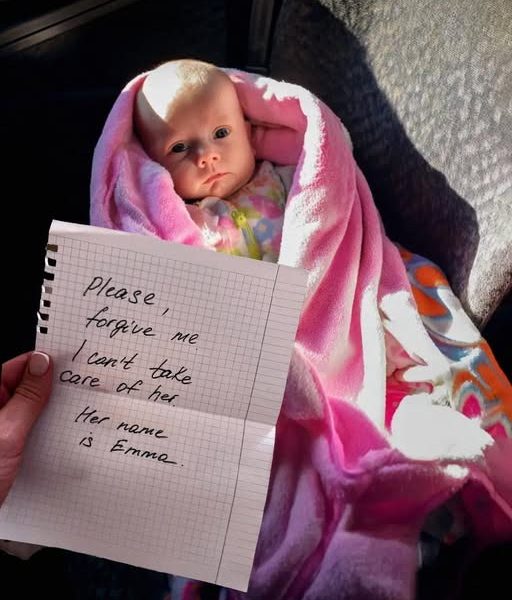

I lunged for the kitchen, Mike right behind me. We tore through cabinets like maniacs. Behind the flour container, my fingers found it: a notebook. *Exposure Therapy Log: Lily* was written in Linda’s perfect handwriting. Mike grabbed it, flipping it open. His face drained of color. “February 15th, Day 1: 5 milligrams ground peanut in chocolate chip cookie. Mild stomach discomfort, as expected.”

My hands shook. I remembered that night. I raced to the ER at 2:00 a.m. with Lily’s little body covered in hives. “You knew?” I screamed. “You watched us panic in that hospital, and you knew!”

My husband, Mike, kept reading, each entry worse than the last. “March 3rd: 2 milligrams. Vomiting occurred, but likely due to excitement from the playground earlier.”

I grabbed my phone, hands trembling as I scrolled through medical records. “Every single ER visit matches your journal entries!”

“I was helping her!” Linda tried to snatch the journal, but Mike held it away. “You’ve made her weak. I was fixing it!”

I pulled up our insurance app. We had paid thousands in medical bills. “$30,000,” I choked out.

“Mommy?” Lily whispered from the doorway, clutching her stuffed bear. “Is that why my tummy always hurts at grandma’s?”

Something inside me shattered.

“The chronic fatigue,” Mike said quietly, still reading. “Dr. Peterson couldn’t explain why she was always exhausted. And the whole time, she was fighting poison.”

I thought about all those work meetings I missed. The promotion that went to someone else because I kept leaving for emergencies. Getting moved to part-time because Lily was always sick.

“The growing pains that weren’t growing pains,” I whispered. “The night terrors, the food anxiety. You caused all of it.”

Mike’s hands shook as he showed me his phone. Her growth chart. “She’s dropped from the 60th percentile to the 30th. Dr. Peterson said, ‘possible malabsorption syndrome,’ but it was inflammation. Two years of my baby’s body attacking itself while this woman took notes like she was conducting a science experiment.”

“Show me page 47,” Linda said suddenly, too calm.

Mike flipped to it. His face went gray. “Consulted with Patricia regarding parental negligence. Parents refuse to acknowledge child’s improving tolerance. May need intervention.” Patricia? I grabbed the journal. At the bottom, in Linda’s writing: *Family law attorney, specializes in grandparent rights.*

My legs almost gave out. Mike caught me. “You were building a case,” he whispered. “Mom, you were… you were going to try to take her.”

Linda straightened her spine. “You’re both hysterical about everything. Someone needs to think rationally about Lily’s future.”

“The autoimmune markers,” Mike said, his voice hollow. “Remember? The specialist said she’s developing autoimmune issues. Unexplained inflammation markers. This… this is why.” Every word was another knife.

The doorbell rang. Linda’s face went white.

“That’ll be Dad,” Mike said coldly. “I texted him. Funny thing about divorce agreements, Mom. Dad kept copies of everything, including that incident with cousin Tony.”

“You wouldn’t.”

The door opened. Mike’s father walked in, took one look at the journal in Mike’s hands, and his face darkened. “Still playing doctor, Linda? I thought you learned your lesson after what you did to Tony.”

“Grandpa Joe!” Lily ran to him.

“Hey, Princess. Why don’t you go play in your room for 10 minutes? The grown-ups need to talk.”

Ten minutes. That’s all we had before Lily would wonder why Mommy was crying, why Daddy’s hands were shaking, why Grandma was packing her things.

“She’ll need therapy,” Joe said quietly, reading the journal. “Years of it. For the trauma, the autoimmune issues, the food anxiety. All of it.”

Linda reached for Lily’s picture on the wall. “You can’t keep her from me. I’m her grandmother.”

“Watch us,” Mike said. “And Linda, that call you’re getting tomorrow? That’s our lawyer.”

As we walked Linda to the door, Lily called from upstairs, “No more grandma’s house!”

My heart shattered completely. “No, baby. No more secrets, ever.”

The door closed. I didn’t know it at the time, but our words had hurt Linda so much that she was ready to use them to destroy our lives forever.

***

I ran to every window in the house while Mike took the stairs two at a time to check on Lily. My hands shook as I twisted each lock and pulled every curtain closed. Joe sat at our kitchen table with Linda’s journal spread open, his face looking ten years older as he read entries we’d missed. He pointed to a page dated six months ago, where Linda had written about testing different delivery methods for the peanut powder.

Mike came back down and said Lily was still asleep, but he’d locked her bedroom window and would sleep on her floor tonight, just in case.

We started tearing through the kitchen like people possessed. I threw every single thing Linda had ever brought into trash bags. Mike pulled out the spice rack and found an old cinnamon container that rattled wrong when he shook it. He unscrewed the lid, and peanut powder poured onto the counter, making both of us jump back. I grabbed the vacuum while he checked inside a vitamin bottle Linda had given us for Lily’s immune system. More ground peanuts, mixed with the vitamins. My stomach turned, thinking about how many times I’d given those to Lily myself.

Joe stayed that night; none of us could handle being alone. He showed us his phone with fifteen voicemails from Linda. He played one where she screamed about us destroying their family and threatened to call every relative we had. Another message said we’d regret this and she knew people who could help her get Lily back.

I grabbed Linda’s journal and started taking pictures of every single page with my phone. Mike set up the scanner and we uploaded everything to three different cloud accounts, plus emailed copies to ourselves. He pulled up our insurance app and started matching every ER visit date to Linda’s journal entries while I could barely hold the papers steady. The pattern was so clear it made me sick. Every single time Lily got sick matched an entry about increasing the dose or trying a new hiding method.

At 3:00 a.m., unable to sleep, I called our pediatrician’s emergency line and left a long message. I explained everything and begged them to send us all of Lily’s medical records immediately. The nurse who called back twenty minutes later promised someone would call first thing and she’d mark it urgent.

When Lily woke up at 7:00, I sat on her bed and tried to find the right words. She asked why Grandma wasn’t here for breakfast like usual on Mondays. I told her Grandma had made a big mistake with the special candy that made her tummy hurt.

“Is Grandma in trouble, like when I drew on the walls that time?” she asked.

I said grown-ups sometimes need to take breaks from each other to think about their choices. Her little face scrunched up, and she asked if it was her fault for eating the candy. My heart broke as I hugged her and promised nothing was ever her fault.

After Lily went back to playing, Mike and I had our first real fight about this. He kept saying he should have seen it, should have protected Lily from his own mother. I yelled that I was her mother and I missed it too, even though I saw her every day. We both ended up crying on the kitchen floor, holding each other. Mike kept apologizing, and I kept saying it wasn’t his fault, while we both knew we’d carry this guilt forever.

Joe came into the kitchen and offered to pay for whatever lawyer we needed. He pulled out a business card for the attorney who handled his divorce from Linda twenty years ago. Then he mentioned he’d kept every document about what Linda did to Tony back then. He said it was all in a safety deposit box and showed us the key. Tony had almost died from Linda’s “treatments” when he was eight, and Joe had photos of him in the hospital.

***

Monday morning came too fast. I had to call my boss about taking emergency leave. She sighed heavily when I said “family emergency” and reminded me about my recent performance issues. I mentioned potential criminal charges against a family member, and suddenly her tone changed completely. She approved one week, unpaid, but made sure to mention my already reduced hours twice.

The pediatrician’s office called back at noon and got us an emergency appointment that afternoon. We drove in silence while Lily played with her tablet, asking why we were going to the doctor again. Dr. Peterson’s face went white when we showed him Linda’s journal. He immediately ordered comprehensive allergy testing, shaking his head and saying he should have suspected something beyond normal childhood illnesses. Then he wrote us a referral to see Dr. Arena Schmidt, who he said was the best pediatric allergist in the state. He called her office himself and got us an appointment for the next morning.

The whole time, Lily sat on the exam table, swinging her legs and asking if she’d need shots today.

Back in the car, I called Lily’s school from the parking lot. The principal gasped when I explained everything and said Linda was banned from the school property immediately. We’d meet tomorrow about a 504 plan. Mike pulled over to text his mom that she couldn’t contact us anymore and everything had to go through lawyers. His phone buzzed back within seconds with a long rant about how we were being dramatic and she had rights as a grandmother. I screenshotted the message and forwarded it to Joe, who was already on his way over with boxes from storage.

That evening, Joe showed up carrying a cardboard box that hadn’t been opened in years. He pulled out folders from his divorce. The psychiatric evaluation from back then described Linda’s boundary issues and her inability to accept medical reality. He showed us hospital records from when Tony was eight and almost died from Linda’s “helping.” Tony had been in the ICU for three days after Linda gave him something she read about online that was supposed to cure his asthma.

Tuesday morning, we sat in the family attorney’s office. She recognized Patricia’s name immediately and said she took the most aggressive grandparent rights cases in the state. The attorney started making notes about preparing for an “inevitable custody battle” and said we needed to document absolutely everything. Then she said something that made my stomach drop: she suggested we call Child Protective Services (CPS) ourselves before Linda could make any claims about us being unfit.

The idea was terrifying, but she said transparency was our best defense. I checked Facebook while Mike asked about restraining orders and saw Linda had already started posting vague things about being kept from her granddaughter, talking about parents who “alienate” grandparents. Mike’s phone started buzzing with texts from relatives asking what was going on. We realized she was building a narrative to make us look like the bad guys.

***

Wednesday morning, we took Lily to get her blood drawn. She completely melted down, screaming about not wanting more “ouchies.” The phlebotomist had to call in two more nurses to help hold her still while she sobbed. I tried to explain that Grandma’s candy had made her sick without scaring her more, but the guilt was crushing. Mike held her other hand, tears running down his own face.

After we got home, my phone rang with a blocked number. It was Jameson McKenna from CPS, calling to schedule a home visit. His voice was professional but cold as he explained they had to investigate all aspects, including our parenting abilities. The visit was scheduled for Friday afternoon.

Thursday, our attorney sent Linda an official cease and desist letter. Within two hours, Patricia responded with her own letter threatening legal action for “grandparent alienation” and demanding regular visitation. The speed of the response showed they’d been preparing this for a while.

Friday morning, we sat in the principal’s conference room for Lily’s 504 plan meeting. The school nurse pulled up her attendance records: 47 days missed in two years, almost all of them Mondays. The pattern jumped out, matching Linda’s journal entries perfectly.

Monday afternoon, we took Lily to her first therapy appointment. “Grandma gave me special brave candy,” Lily told the therapist, making a toy elephant walk across the carpet. “Am I still brave without the candy?” she asked, looking up with those big eyes. My heart cracked right down the middle.

Wednesday afternoon, Jameson and his supervisor showed up for the CPS home visit. They walked through every room, taking photos and notes. Jameson checked our food storage, while his supervisor counted the EpiPens we’d stationed throughout the house. The whole visit took three hours and left us feeling exposed and judged.

That same night, around 10 p.m., two police officers knocked on our door, saying they’d received a report about medical neglect. Mike showed them the CPS visit report from earlier. The officers looked tired and annoyed once they understood. They made a quick report and told us to call if Linda showed up.

Thursday, we finally met with Dr. Schmidt. She spread the lab reports across her desk. Lily’s peanut allergy was off the charts. Plus, she’d developed new sensitivities to tree nuts and sesame from the repeated exposure. Dr. Schmidt explained how Linda’s hidden doses had caused Lily’s immune system to go haywire. “She could have died any of those times,” she said quietly. The worst part was learning the damage might be permanent. She prepared a detailed, 12-page medical report linking every symptom to the peanut exposure. “This was deliberate harm,” she said. “I’ll testify in court if you need me.”

Our attorney filed for an emergency protective order that afternoon. The hearing was set for next Tuesday. Mike’s phone started blowing up within an hour. His aunt called, saying Linda was “misunderstood.” His brother texted that he’d never let Linda babysit his kids because something always felt “off.” The family group chat turned into a war zone.

Friday morning, Mike got called into his boss’s office. She’d printed out his phone records, showing all the personal calls during the crisis. She slid a written warning across the desk and told him to get his home life together. The warning put him on probation for 90 days. That afternoon, we got a letter from our insurance company denying coverage for Lily’s new allergy treatments, calling the protocol “experimental.” We put $3,000 on credit cards to pay for her first month of medications.

The next morning, Lily’s therapist called. She described watching Lily inspect every single Goldfish cracker for ten minutes, asking if someone put something bad inside. She now refused to eat anything she hadn’t watched being prepared. The therapist said this level of food anxiety was a trauma response from two years of being secretly poisoned.

***

Two days later, we sat in the CPS office while Jameson interviewed Lily. Through the observation window, I watched my daughter tell him about the “special candy” that made her tummy hurt, but Grandma said she was brave for eating it. I saw his jaw tighten when Lily described throwing up and being told not to tell Mommy because it would make me sad.

The next week, Joe drove three hours to meet with CPS investigators, bringing two file boxes. He handed over hospital records from 25 years ago, showing his nephew Tony hospitalized five times while under Linda’s care for unexplained illnesses. The similarities to Lily’s history were chilling. Tony himself sent his adult medical records, detailing ongoing digestive problems and severe food anxiety. His written statement described Linda making him eat foods that made him sick because she believed it would “cure his weakness.” Reading how he still can’t eat certain foods without panic attacks 20 years later made me run to the bathroom and throw up.

Three days after that, the school principal called. Linda had shown up, claiming a family emergency and demanding to take Lily home. The office staff followed our safety protocol and refused. Security footage showed Linda pacing in the lobby before finally leaving when the resource officer approached. We filed another police report.

Patricia’s formal petition arrived two days later: thirty pages painting us as unstable parents who were alienating a loving grandmother. She demanded immediate visitation rights and suggested we needed psychological evaluations.

The emergency protective order hearing came two weeks later. The judge reviewed Linda’s journal, the CPS reports, and the medical evidence. He granted temporary protection but also ordered a family evaluation by a court-appointed psychologist and said Linda could have supervised visitation at a court facility pending the investigation. Our attorney called it a partial victory, but it felt like being punched in the stomach.

The following Saturday, we attended a friend’s birthday party. When they brought out peanut butter cookies, Lily started screaming that they were “bad candy” and hid under the picnic table. Other parents stared as I crawled under to hold her while she sobbed. We left within ten minutes.

Monday morning, my boss called me into her office. A performance improvement plan sat on her desk, outlining my excessive absences and lack of focus. I had 90 days to show improvement or face termination. I spent my lunch break in my car researching FMLA paperwork.

Mike found a support group. After his first meeting, he came home and sat at the kitchen table for ten minutes without saying anything. Finally, he looked up and told me he’d been making excuses for Linda his whole life. The group leader had asked him to list times his mom crossed boundaries; Mike filled three pages just from the last five years. He realized he’d trained himself to ignore red flags because admitting them meant admitting his mom was dangerous.

The next day, Linda started her Facebook campaign. She shared articles about food allergies being “overblown” and kids needing to “toughen up.” Each post got dozens of likes from her friends and our relatives. Our attorney told us not to engage. I blocked fifteen people that week.

A follow-up with Dr. Schmidt showed Lily’s inflammation markers were still at dangerous levels. Her body was still attacking itself. The new medications cost $400 after insurance.

A few days later, Jameson from CPS called. He’d finished his preliminary investigation and was recommending no unsupervised contact between Linda and Lily. His official report arrived a week later, stating “substantiated child endangerment” in black and white.

Two weeks later, Patricia hit us with subpoenas for our financial records, trying to prove we were somehow profiting from keeping Linda away. We spent eight hours gathering documents.

The court-ordered mediation happened three weeks later. Linda insisted she’d been helping Lily and refused to acknowledge any wrongdoing. The mediator ended the session after two hours, writing that reconciliation seemed impossible.

That weekend, CPS filed their official report with the court, recommending no unsupervised access and a psychiatric evaluation for Linda, citing “significant risk of continued harm.”

Five days later, I found a gift bag on our porch. Inside were Lily’s favorite toys from Linda’s house and a note: “I forgive you for keeping her from me.” We called the police. It was a clear violation of the protective order.

That night, Joe called. He’d testify at the final hearing. He knew it would destroy what was left of his relationship with Linda’s family, but he said protecting Lily mattered more. He wouldn’t make the same mistake he made with Tony twenty years ago.

***

The night before the final hearing, Mike and I sat at our kitchen table surrounded by documents. Neither of us slept.

The next morning in the courthouse, Linda sat with Patricia, wearing a soft pink cardigan and a pearl necklace, looking like she was going to church.

Our attorney laid out the evidence: Linda’s journal, the $30,000 in medical bills, the CPS report, and a timeline overlaying Linda’s entries with Lily’s ER visits.

Linda took the stand and cried softly, claiming she was just trying to help her granddaughter. Patricia painted us as helicopter parents.

Jameson testified next, calm and professional, confirming Lily’s story and the hidden peanut products. He stated that Linda posed a “significant risk of continued harm.”

Dr. Schmidt testified last. Her testimony was devastating. She explained how real exposure therapy works under strict medical supervision and held up a visual showing the medical dose versus what Linda had been giving Lily—hundreds of times larger. She detailed the potentially permanent damage to Lily’s immune system.

The judge took a 20-minute recess before announcing his decision. They were the longest 20 minutes of my life. When he returned, he denied Linda’s petition for grandparent rights completely and upheld the protective order for one full year. He used the words “reckless endangerment” and “deliberate harm.” Linda sobbed loudly as Patricia gathered their papers. I felt nothing but relief.

Within hours, the messages from Linda’s family started, calling us monsters. We spent the evening blocking people, shielding Lily from the fact that half her extended family now hated us.

Two weeks later, CPS closed our case with a safety plan in place. Jameson said he’d never seen such clear documentation of intentional harm in a grandparent case before.

Three months passed. One night at dinner, Lily ate her entire meal without asking what was in it. It was a breakthrough. The food anxiety wouldn’t disappear overnight, but seeing her eat without fear made me cry happy tears.

Our financial advisor looked grim when we reviewed the damage: $45,000 in medical bills, legal fees, and ongoing therapy. It meant putting off buying a house for at least five more years.

Mike and I started couple’s therapy. We learned to talk without blame and recognize triggers. We scheduled weekly sessions and left holding hands for the first time in days.

Joe started visiting on Sundays. We met him at the park with clear rules: no Linda talk, no food. He brought watercolors, and he and Lily painted side-by-side for an hour.

The school finalized Lily’s 504 plan, with a bright red alert in their system about Linda. I filled out FMLA paperwork at my job, which was legally protected, much to my boss’s annoyance.

Wednesday’s mail brought a three-page “apology” letter from Linda, filled with justifications and ending with a prayer that we’d “come to our senses.” Our attorney said it was a paper trail for future legal action. We filed it with everything else.

That Saturday, Lily looked up from her plate and asked, “Does Grandma Linda still love me, even though she made me sick?”

We’d practiced this with her therapist. I told her that sometimes people who love us don’t know how to show it safely. Mike added that loving someone doesn’t mean we have to let them hurt us. Lily seemed to understand and went back to eating.

Six months after that horrible dinner, our life was different but steadier. Lily’s weight was back in the 45th percentile. Mike and I were talking again. The bills still crushed us, but Lily’s health was worth any price. Joe came every Sunday with art supplies, and our fridge was covered with Lily’s paintings of trees, flowers, and one small picture of a house with no grandma inside. We’d built new routines and boundaries that kept Linda’s poison out. The scars she left would last forever, but we were learning to live with them, protecting our daughter one careful day at a time.